Just a reminder of my newsletter, available in English and Spanish. Let's continue the conversation there!

Monday, March 25, 2024

Friday, March 8, 2024

Newsletter in English and Spanish

I've just launched a newsletter in both English and Spanish. I'll keep posting on this blog, but if you want to get regular updates, follow me there.

Here's the first installment:

Maturity and Enthusiasm

(An introduction to this newsletter about information design, visualization, data reasoning, and many other related topics.)

In What is Philosophy?, Félix Guattari and Gilles Deleuze wrote that old age gives us “not an eternal youth, but a sovereign freedom, a pure necessity in which one enjoys a moment of grace between life and death, and in which all the pieces of the machine fit together to send into the future a message that spans the ages.”

Towards the end of 2021, despite being far from old in the conventional, quantitative sense of the word, I felt a cold breath on the back of my neck, a glimpse of death on the distant horizon. Perhaps as a consequence of that, I also had some moments of insight and grace similar to those experienced by the venerable French thinkers above. Many pieces of my machine fell into place.

In the company of many designers whose work I admire, I poured those pieces and my thoughts about them into a book, The Art of Insight (November 2023), which is a message into the future, like that of Guattari and Deleuze.

This newsletter is a continuation of that book.

It's not just that I’ve reached a certain professional wisdom (or so I hope!), but also that the profession and the language (the visual language) to which I have devoted my career have also matured. However, despite the increasing popularity of data visualization and information design, they are still niche domains. There’s much to be done for them to become widespread and democratized, which is, in essence, the core and sole goal of my career.

As I’ve said in conferences over the last decade, anyone can benefit from learning to design information. Like being able to write with fluency, knowing how to design not only makes us better communicators but also helps us think better—more clearly and deeply. Design is an aid to reasoning.

I write these lines after teaching a workshop on data visualization and information design to professors and doctoral students at the Universidad Iberoamericana in Mexico City. I observed what I often see in all my classes: minds opening to new worlds, the discovery of a universe of possibilities, and the surprising realization that designing visualizations is not so complicated after we grasp some fundamentals of their vocabulary and grammar.

Teaching this type of workshop—sharing the little I know with others—is intoxicating. It excites me. I want more.

Enough rambling. What will you find in this newsletter, which I hope will have a reasonable frequency? A bit of everything: analysis of infographics and visualizations that catch my attention; recommendations and reviews of books; conversations with visualization creators; musings about the craft and about life in general...

The description of this newsletter indicates that this will be a very personal and idiosyncratic space. That’s not big news. In The Art of Insight I said that the intention of all my books, classes, presentations, or consulting engagements is not to teach how to design visualizations but how I design visualizations, my motivations and reasons to think about and create graphics in a certain way—which is not the only way. There are others.

(In the near future I will also share information about new talks and workshops that I’m putting together; get in touch if you want to learn more about them right away.)

I hope you’ll join me on this journey. I believe it will be long because it has no predetermined course or destination. Instead, let’s enjoy every instant, feeling the sun on our skins, the wind on our faces, and salt on our lips.

I conclude the first installment of this newsletter with a thought: It isn’t a bad idea to do our best to live a life worthy of a song like this, written by Sharon Robinson after the passing of her friend Leonard Cohen:

Monday, December 11, 2023

Spain's Eldiario.es visualizes how inequality persists

Notice the combination of different types of charts —dot maps, scatter plots, stacked bar graphs,— the effective annotations and highlights that emphasize the main points of the narrative, the use of color, and the addition of individual stories to exemplify the patterns displayed in the visualizations. It's pretty good!

Tuesday, November 28, 2023

Podcast interviews

I very much enjoyed these conversations —I think that you'll notice that. In all of them I went way beyond the book itself. This is useful, as talking to people gives me new ideas of what to think about (and, eventually, write about) in the future.

Friday, November 17, 2023

An interview with Mona Chalabi

“When I first started doing this, everyone was just like: what a load of bullshit. [...] Everyone else was building these really complicated data interactives and that was seen as the cutting edge and the fact that I was drawing it was seen as feminine. It was seen as innocuous.”

In the Epilogue of The Art of Insight I included a similar quote from a sobering essay by Federica Fragapane:

“I’ve started noticing a phenomenon: projects of mine about women rights/women rights violations are more likely to attract technical — and sometimes unkind — remarks from men. That’s an interesting pattern.

What strikes me the most is how such comments completely ignore the topic to jump directly to technical considerations: data on rights violations take second place to the fact that “it should have been a bar chart”. I’m convinced it’s possible to do both: constructively criticizing and being respectful. But I also think that this is part of a broader issue that finds its roots in a common practice: delegitimisation.

Delegitimisation of a subject, delegitimisation of an approach, delegitimisation of a voice: I think it can be a more or less conscious attitude. I like to observe phenomena and to find patterns — it’s part of my job — and I also like to point them out and to discuss them: because those comments don’t particularly bother me, but they could bother others. They could intimidate other people who are trying to find their voice, they could shut them up. And of course I’m not only talking about women, I’m aware of how variegated are the obstacles that people stumble across only for their identity, the walls they find.”

I've been the type of person that Federica describes. We must strive to do better.

Saturday, November 11, 2023

Something I've just sent to a reporter

Some lines that I've just sent to a reporter:

The Art of Insight is my most personal book to date, a tribute to the people who design infographics and data visualizations to make the world a more knowledgeable and beautiful place.

After writing books about visualization from a more technical perspective (The Truthful Art) or to inform the general public about how we often misinterpret charts (How Charts Lie) I felt that I needed to do a book for myself that would rekindle my passion for the craft that I've dedicated my life to.

Writing The Art of Insight has been therapeutic and healing. I wish that it'll help newcomers feel as enthusiastic as I am about graphics when they learn about the lives of others who've worked in this field for years.

(In other words, if you design visualizations, The Art of Insight is my tribute to you.)

Wednesday, November 8, 2023

A conversation with Nick Desbarats

Nick Desbarats is a visualization educator and consultant who has a new book coming out on November 15, Practical Charts. This is the exact same official publication date for The Art of Insight (I wrote “official” because it's already available for purchase and delivery on Amazon.)

Nick and I decided to interview each other. The conversation was a lot of fun, and Nick's book is fantastic, so I suggest you don't miss it:

Monday, November 6, 2023

'The Art of Insight' has arrived

Touching and browsing through The Art of Insight feels like the end of a journey. While writing it I thought that this would be my last word about visualization and infographics; I've said a lot —perhaps too much— about our trade already, and I've often wondered whether it's time to shut my mouth and instead help raise younger, fresher, and wiser voices —as a book editor, for instance, a job that I greatly enjoy.

(In his enthusiastic review of The Art of Insight, Frank Elavsky wrote that I'm “a caretaker of the lost.” That's the highest praise I've ever received, I believe. Indeed, if you feel lost, I'm here to help —but please send me your book pitch, too!)

What comes next? On the one hand, I wish to write about topics that have nothing to do with graphics. On the other, at the end of The Art of Insight I hint that there's a new idea sloshing and slowly taking shape inside my skull, so who knows; time with tell.

Saturday, September 30, 2023

Read part of 'The Art of Insight' NOW

Thursday, June 15, 2023

I've just finished writing 'The Art of Insight'

I've just written the last line of The Art of Insight. Now begins the long process of copy-editing and production that will finish on November 15, 2023, its publication date.

The Art of Insight is two years late. Never in my life I've missed so many deadlines (this book exists thanks to the generosity and patience of the good folks at Wiley,) and never before I've faced a task that looked so insurmountable so often. But I'm reasonably happy with the results and, ultimately, that's all that matters. I hope you'll like it.

Saturday, May 13, 2023

A few early blurbs for 'The Art of Insight' are in

In just a month I'll send last third of The Art of Insight to my publisher, Wiley; the publication date is still November 14 this year. If you want to get a glimpse of what my quirkiest, most personal, and most meandering book to date contains, these early blurbs might provide a few clues (more are on their way):

Data visualization books don't typically transport you to new worlds. Alberto Cairo's latest book delves into the lives of numerous designers, learning more about what shaped the designer and their respective works. Each chapter showcases stunning examples, but also life stories and the motivations that informed choices. I laughed, I cried, I cheered, but perhaps most importantly, I caught glimpses of myself and my own story. —Bridget Cogley, co-author of Functional Aesthetics for Data Visualization and Chief Visualization Officer at Versalytix

Visualization stretches beyond reports and sterile charts to uses more tightly coupled with real life, which is full of beauty, complexity, and stories. With The Art of Insight, Alberto Cairo places the full field on display. Learn the design and analysis processes of those in less traditional visualization roles, alongside Alberto's unique perspective, and your own data work will benefit, wherever that may be. —Nathan Yau, Statistician, FlowingData

Another amazing book by Alberto Cairo. It presents a broad overview of contemporary visualization practices through a plurality of voices that are diverse and culturally rich. Conversations with key visualizers from around the globe are interwoven with insights and acuity from Cairo’s deep and vast knowledge of the field. The book is a must for practitioners and students alike as we are introduced to a variety of approaches to representing data, including first-hand experiences guided by the author's generous views. What a joy! —Isabel Meirelles, Professor, OCAD University, and author of Design for Information

The Art of Insight is an inspiring collection of tales of forms and shapes. Not the forms and shapes that make up beautiful art and visualization but the journeys that formed and shaped the visualization artists behind them. In Cairo's book, visualization artists reflect on their diverse backgrounds, inspirational sources, and haphazard career paths. They share insights into their thought processes, their sources of inspiration, and both the little and big things in life that influence them. The book provides wonderful insights into the conscious and sometimes unconscious steps that preceded the artists' creations. By providing a lens into how these artists were formed, the reader is left feeling encouraged to embrace their own journey into the world of graphical visualization. —Claus Thorn Ekstrøm, Professor of Biostatistics at the Department of Public Health, University of Copenhagen

I’ve been a fan of Alberto Cairo’s work for years, and his new book The Art of Insight is a delightful addition to his body of work. I enjoyed his conversations with designers from around the world about their histories, their evolution as artists and artisans, and their insights about their work in visualization. Examples ranged from the humorous to the tragic. I’m grateful to Alberto for sharing his conversations with these brilliant visualization designers and for the inspiration for all of us who share the goal of creating visualizations that carry meaning to an audience. —A. John Bailer, Professor Emeritus of Statistics, Miami University; Past-President of the International Statistical Institute; Stats+Stories podcast host; Author Statistics Behind the Headlines

Saturday, March 25, 2023

CRC's Visualization videocast

CRC has also created a free e-book with sample chapters from several of those books. Get it here.

I very much enjoy working with other authors, so if you have an idea for a book about information design, data visualization, data journalism, or related topics, let me or Tamara know. We're here to help.

Tuesday, March 14, 2023

Playing with ChatGPT while writing 'The Art of Insight'

For reasons that will become clear when you read the chapter (the book should be out by late November,) I'm mentioning philosopher Martha Nussbaum, particularly her The Therapy of Desire, which discusses the Hellenistic philosophers, Epicureans, Stoics, and Skeptics.

In one of my breaks it occurred to me that I could ask ChatGPT to generate an essay summarizing Nussbaum's book. The results aren't bad! Maybe I should prompt the tool to write The Art of Insight for me and go on vacation in the meantime:

Martha Nussbaum is a prominent contemporary philosopher who has made significant contributions to the study of Hellenistic philosophy. Her views on Hellenistic philosophy are grounded in her belief that these ancient thinkers offer valuable insights into questions of ethical and political life that remain relevant today. In this essay, I will explore Nussbaum's views on Hellenistic philosophers, focusing on their theories of ethics and their relevance to contemporary discussions about human flourishing.

Nussbaum's approach to Hellenistic philosophy is influenced by her training in the study of classics and her interest in the practical applications of philosophical ideas. She argues that the Hellenistic philosophers, particularly the Stoics, Epicureans, and Skeptics, were concerned with questions of how to live a good life and how to achieve a state of flourishing, or eudaimonia. These thinkers believed that the pursuit of eudaimonia required the cultivation of certain virtues, such as wisdom, courage, and justice, as well as a sense of inner calm and contentment.

One of the key insights of Hellenistic philosophy, according to Nussbaum, is the idea that ethical and political questions cannot be separated from questions of human psychology and emotion. The Hellenistic philosophers recognized that human beings are emotional creatures, and that our emotions can either help or hinder our pursuit of a good life. For example, the Stoics believed that the key to achieving inner calm and contentment was to cultivate a sense of detachment from external goods and to focus on developing virtues such as wisdom and courage. The Epicureans, on the other hand, emphasized the importance of pleasure and argued that the pursuit of pleasure was the ultimate goal of life, as long as it was pursued in moderation and without harming others.

Nussbaum argues that the Hellenistic philosophers' emphasis on the importance of emotions and psychology has important implications for contemporary discussions about human flourishing. She believes that their ideas can help us to better understand the nature of happiness and to develop more nuanced and effective approaches to promoting human well-being. For example, Nussbaum argues that the Stoic concept of detachment can help us to cope with the challenges of modern life, such as stress and anxiety, by encouraging us to focus on what is within our control and to let go of our attachment to external goods. Similarly, the Epicurean emphasis on the importance of pleasure can help us to recognize the value of enjoyment and to avoid the trap of excessive consumption and materialism.

Overall, Nussbaum's views on Hellenistic philosophy offer a valuable perspective on the nature of human flourishing and the role of emotions and psychology in ethical and political life. By emphasizing the importance of cultivating virtues and developing a sense of inner calm and contentment, the Hellenistic philosophers offer a compelling vision of a good life that is both achievable and meaningful. Nussbaum's work demonstrates the continued relevance of these ancient ideas and their potential to enrich our understanding of human well-being and flourishing.

Monday, February 27, 2023

What 'The Art of Insight' is about

Yesterday I announced in social media that I've written half of The Art of Insight already. It should be out by late November this year. Some people asked how it's different to my previous books. It's very different —much more personal and idiosyncratic. It's both an attempt to reignite my love for the craft and also my tribute to its practitioners.

In case you're interested, here's the first draft of the opening two pages (this hasn't been edited, so ignore typos and ungrammatical sentences):

Preamble

On Magic

To live well is to cope with the ways in which life is hard while finding enough in one’s life worth wanting. —Kieran Setiya

One early morning in November of 2021, Alex, my youngest son, questioned me about the apparent meaninglessness of life: “Why are we humans here for anyway?”

Alex has been a precocious old soul since he learned to talk. The week when I was working on this preamble he wrote an autobiographical poem that contained a haunting alliteration to define who he is: “I’m a lover of darkness, dragons, and dreams.”

At the time of our conversation we were both coming to terms with that darkness: healing, mustering our dragons for battle, and rebuilding our dreams. The pandemic years had been tough.

I remember myself thinking in silence for a moment. We were in our morning commute. Alex, sitting in the back of the car, was looking out at parents and kids passing by on their way to school. He was in a somber mood, and I guess he wasn’t expecting a quick answer from dad, who’s usually so aloof and introverted.

But my answer poured out like a torrent. Life, I said, is indeed meaningless in itself. Meaning isn’t a predetermined thing that exists beyond ourselves and our connections to others, or that we receive from imaginary higher powers. Meaning is something that we build by living through the myriad of little but immensely relevant events that cross our paths. It emerges from paying deep attention to the joys and beauty offered by the objects, creatures, and people whom we love, and by sharing back with them. That’s all there is to a good life brimming with magic.

Alex’s reply was a soft murmur.

I parked at school and noticed that my son was staring at a fence next to us. There was movement on it.

Alex suddenly yelled, his voice a mixture of excitement and wonderment: “Dad, look, songbirds!” Indeed, there they were, two merry critters standing on the wire, chirping at each other while ignoring the multitude below.

I smiled. “See? That’s what I meant. That’s the magic.”

• • •

This is a book about such magic. To write it, I spoke with many magicians, visualization designers who build meaning as a tribute to themselves or as an aid to others. They make things, they enjoy the process and, by sharing its results, they brighten the world.

Some of these designers are old friends; others are people whose work I’ve found fascinating more recently. They are data scientists, engineers, analysts, humanists, artists, journalists, and educators, each with their own views about the practice.

My sample for this book isn’t representative of anything outside of my head. The designers you’re about to meet are the first who came to my mind when I felt the need to rekindle my love for the design of information, the craft to which I’ve devoted my professional life. A half-joking alternative title I entertained was On the Consolation of Visualization, as a nod to Boethius’s famous On the Consolation of Philosophy. The list of people whose work I find interesting, inspiring, or intriguing is much longer, though; should I’d had more pages and time, I’d have reached out to many more of them to seek solace.

This is also a book about insight. Not in the sense of data-driven analytical insight; there are plenty of books in the market about that, including some I’ve written myself. This book is different. I use the term “insight” in the sense of exploring who the designers I spoke with are and how they see themselves. I’m interested in how they shape their craft, how the craft shapes them in return, and how such interaction creates an ethos.

Finally, I envision this book as one link in the broader chain of historical conversations about information design and visualization. It’s the result of the interaction between what my interlocutors told me, past readings that were brought back to memory during our chats, and my reflections about both. I’ve ended up writing an essay in the literal sense of the term: a way to essay ideas, to contemplate them in a nonjudgmental manner with no expectation of reaching conclusions, of inferring overarching lessons, or —the gods forbid the hubris— of developing a coherent system of thought. The philosopher Joan-Carles Mèlich calls this approach to thinking and writing “the wisdom of the uncertain.”

This The Art of Insight is, then, a wandering, and not a solitary one.

Friday, February 24, 2023

How we lie to ourselves with charts about LGBTQ issues

In the past few years I've become increasingly alarmed about how journalists cover the transgender community, particularly transgender youth. Being interested in graphics, I decided to record the following short and informal talk about a specific set of charts that I often see misused and even weaponized against one of the most vulnerable minorities in this country. Jon Schwabish has also written about one of them.

(Note: I recorded this in 15 minutes this morning after a friend was contacted by a large news organization asking about several things, this chart among them. Instead of writing a long answer, I quickly recorded a video for her so she could share it. That explains the just-OK quality. You can download the slides here.)

Wednesday, February 22, 2023

Visualization “thought leaders” don't know much

In the Fall of 2014 Lena Groeger, the graphics director at ProPublica, emailed me to ask about a project she was working on. It was a visualization of the compensation that U.S. workers receive for damaged body parts; the amount depends on the state where the worker is. Lena wanted my opinion about using “a little person that represents each state, and size each body part according to difference from the national average.”

My reaction was quick and visceral. I replied that I wouldn't do it because it looked creepy and her illustrations sent “shivers down my spine.” Instead I recommended to use traditional maps and graphs.

Lena is a wise journalist and designer, so she chose to ignore me. The result was one of the most widely read graphics she's ever created. It was picked up by multiple news organizations —Gawker linked to it with the title 'How Much Are Your Balls Worth?'— and led to discussions about policy in several states.

Think about this anecdote whenever visualization “thought leaders” —I've always rejected that label, as it really sends shivers down my spine— claim to know what we're talking about.

Monday, February 20, 2023

Sociopathic journalism

A week ago a large number of New York Times contributors and tens of thousands of their readers signed an open letter criticizing the newspaper's coverage of youth gender-affirming care. I was among them. I've written about these matters in the past (here and here,) and I'll likely keep doing so in the future. I've also argued that some reporters covering this care don't know how to reason under uncertainty —or they pretend not to know.

The Times's response to the letter was not only tone-deaf, but also a perfect example of a common malady in journalism, a certain sociopathic temperament. Some cases of this malady are acute; there are people who have built lucrative careers out of seeding doubt and muddling the waters. Shame on them.

One of the challenges with journalism is that its ethical codes rely too much on deontological and virtue ethics tropes, and too little on consequentialist thinking. In J-school we are taught the conventions and rules of the trade, and we're encouraged to become virtuous First Amendment warriors and “truth-tellers”. However, we're taught too little about the complexities of the very word “truth”; or about how our “truth-telling” is extremely selective; or about how it can negatively impact those whom we write about.

Proper applied ethics requires a careful balancing of those three moral reasoning strands. Journalism can learn a thing or two from design ethics: Think of news stories as tools that mediate between the complex world out there and the minds of readers. Whoever writes a news story should be, at a minimum, partially responsible for how that story is used or misused.

And we know that the inaccurate and sensationalistic coverage of gender-affirming care is being weaponized. For instance, some profoundly biased pieces that have appeared in The New York Times and other publications have been used to support arguments to deprive people of care they need. That's the core of the letter's criticism. Reporters and their editors must do some soul-searching. It's way past due. They are fueling a moral panic.

Instead, the Times has doubled down, which isn't that surprising, as elite journalism isn't just often sociopathic, but also hubristic and brazen. Joyce Carol Oates has accurately described it: “Mainstream media seizes upon highly atypical, microscopic samples of an issue that affects virtually no one, amplifies it maniacally, continues to focus upon it as if it were some sort of threat to the commonwealth, & not an amplified paranoid-figment of media imagination.”

The Onion has a poignant and fierce piece about this topic. If you teach news ethics, I suggest that you add it to your recommended readings list.

Anyway, this week I've been working on the chapter of The Art of Insight about Alyssa Fowers, who I think represents a much better type of journalist. Alyssa has a wonderful blog and is also a graphics editor at The Washington Post. Here are a few paragraphs:

Too often in my journalism career I’ve seen reporters who don’t think much about the impact that their reporting might have in the people they cover. They treat them as subjects, numbers, things to be explored, analyzed, understood in a detached, statistical, sanitized manner.

Recently —I’m writing this in early 2023,— we’re witnessing this sociopathic behavior in the way that mainstream media covers transgender people, particularly transgender youth, their access to gender-affirming care, and their increasing presence and visibility in society. These topics are often framed as a sensationalistic “debate” or a “controversy,” and not as what they truly are, human rights. This is insulting, demeaning, and dehumanizing.

I’d say that it’s also the opposite of Alyssa’s approach. I think that she’s representative of a generation of journalists who try not only to get their data right, and to present it as accurately and fairly as possible, but who are also emotionally invested in their stories. Theirs is a journalism that transgresses dusty notions of journalistic objectivity and that, as a result, becomes better, more humane.

A story that Alyssa contributed to, which describes how the COVID pandemic worsened the mental health of transgender people, showcased elegant variations of Sankey diagrams and bar graphs, but its focus isn't these graphics or the numbers behind them. To me, the writing and visual style signal a profound empathy towards the people whose lives are being written about and visualized.

Essayist Rebecca Solnit once wrote that “empathy is first of all an act of imagination, a storyteller’s art” because it consists of imagining ourselves in somebody else’s place. Maybe that should be a requirement to all who gather, analyze, visualize, or write about data about other human beings.

Thursday, January 12, 2023

A sneak peek of 'The Art of Insight'

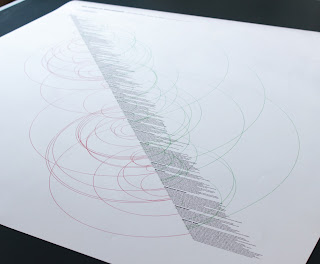

I've just finished the first draft of 2/5 of The Art of Insight. This week I'll be sending it to some friends to get some feedback. I printed it out to edit it myself. The book will be launched late in November this year.

Here's a short video:

Friday, December 30, 2022

Quotes in 'The Art of Insight'

All my books contain quotes prefacing sections and chapters. These quotes are deliberately chosen to be connected to the themes I write about, or to subtly hint things without saying them explicitly. Below I've collected the quotes in the first third of The Art of Insight, which I'm finishing these days:

Take advice to ditch all adverbs lightly. —Ursula K. Le Guin

Enjoy and have others enjoy, without doing harm to yourself or anyone else; that is all there is to morality. —Nicolas Chamfort

I have sought only reasons to transcend our darkest nihilism. Not, I would add, through virtue, nor because of some rare elevation of the spirit, but from an instinctive fidelity to a light in which I was born, and in which for thousands of years men have learned to welcome life even in suffering. —Albert Camus

Being a person is not a goal that can be achieved but a purpose to be sustained. —Martin Hägglund

It is not doctrines that console us in the end, but people: their example, their singularity, their courage and steadfastness, their being with us when we need them the most. In dark times, nothing so abstract as faith in History, Progress, Salvation, or Revolution will do us much good. These are doctrines. It is people we need, people whose examples show us what it means to go on, to keep going, despite everything. —Michael Ignatieff

The lover of life’s not a sinner. —Black Sabbath

To live well is to cope with the ways in which life is hard while finding enough in one’s life worth wanting. —Kieran Setiya

There are three rules for writing the novel. Unfortunately, no one knows what they are. —Popularly, and probably posthumously attributed to Somerset Maugham

There are no absolute truths, there is nothing Good, Bad, True, Beautiful, or Just in itself, but only relatively, evaluated according to a clear and distinct plan [...] Think in terms of action, and base your actions on the effects they will have. —Michel Onfray

The word [normal] uses a power as old as Aristotle to bridge the fact/value distinction, whispering in your ear that what is normal is also right. —Ian Hacking

[There’s a] difference between defining beauty and defining what beauty does in the body. The latter question belongs to the realm of aesthetics, the study of bodies in proximity to beauty. —Chloé Cooper Jones

To cultivate [the] diverse elements of our existence means to nurture them as we would a garden. Just as a garden needs to be protected, tended, and cared for, so do ethical integrity, focused awareness, and understanding [...] There is no room for complacency, for they all bear a tag that declares: “Cultivate Me.” —Stephen Batchelor

Trees fall with spectacular crashes. But planting is silent and growth is invisible. —Richard Powers

We are ready to question the impersonality of a merely technical approach to data and to begin designing ways to connect numbers to what they really stand for: knowledge, behaviors, people. —Giorgia Lupi

I think of the wood warbler, a small citrus-colored bird fast disappearing from British forests. It is one thing to show the statistical facts about this species’ decline. It is another thing to communicate to people what experience of a wood that is made of light and leaves and song becomes something less complex, less magical, just less, once the warblers are gone. —Helen MacDonald

Objectivity of whatever kind is not the test of reality. It is just one way of understanding reality [...] Sometimes, in the philosophy of mind but also elsewhere, the truth is not to be found by travelling as far away from one persona perspective as possible. —Thomas Nagel

Saturday, December 24, 2022

Revisiting Robert Grudin for 'The Art of Insight'

On insight:

Of all the kinds of joy, none perhaps is so pure as that occasioned by sudden insight. To come to terms independently with a new idea is to celebrate, in the broadest sense of the word, the reality of nature and to appreciate fully one's own human presence. But creativity does not confine itself to happy subjects, or always bring happy results. Too many examples of tragic vision, or of genius in the service of malice, argue the contrary. Moreover, though creative insight may be delightful in itself, it normally is predicated on training, prolonged concentration, and exhausting practice that are not pleasant in the same sense.

On our sense of beauty:

Our sense of beauty is generally restricted to those categories (art, music, love, nature) to which aesthetic language is applied by our culture. But independent insight in all fields involves in some way the experience of beauty. In fact, the thrill conveyed by inspiration in any field is perhaps best described as coming from a sense of participation in beauty, a momentary unity between a perceived beauty of experience and a perceiving beauty of mind.

Much later in the book:

Beauty oddly resembles gravity: like gravity, beauty is a force whose existence is inferred from its apparent effects.

A page later:

Joyce sees beauty not as simple quality but as a function of the relation between subject and object. When a given object is properly understood (exquisite, adjusted), its beauty leaps out to the person who understands it. Beauty, therefore, is not a wholly independent force; neither, however, is it an illusion or social convention or mere “effect” of object upon subject. It is rather the natural and necessary consequence of the proper interaction between subject and object or, if you will, between mind and reality.

About innovation and inspiration:

It is striking how many noted revolutionaries and innovators insist that they are maintaining continuity with the past or restoring old ideas that have been corrupted or forgotten [...] Inspiration may be the revelation of something completely new, but it is also the rediscovery of something always true.

About the burden of the past:

Preconceptions can militate against valid insight; investigators who insist on building exclusively upon past findings equip themselves for defeat.

One of my favorites, about the relationship between humor and insight:

Humorless people are unlikely to discover much. They are usually more concerned with their own dignity and rectitude than with anything going on around them. Unavailable to the sudden analogies and anomalies that cause laughter, they are apt to be dull toward other analogies and anomalies as well. Blind to their own humanity, they respond sluggishly to all other experience.